Contents:

Special Category Status

The concept of Special Category Status (SCS) in India was introduced in 1969 to address regional disparities by providing preferential treatment to certain states in the form of central assistance and tax breaks. They are considered special because they face unique socio-economic and geographical challenges, have high production costs with limited availability of useful resources, and consequently have a low economic base for livelihood activities.

Special Category Status for plan assistance was granted in the past by the National Development Council (NDC) to the States that are characterized by the following criteria:

- Hilly and difficult terrain;

- Low Population Density and/or Sizeable Share of Tribal Population;

- Strategic Location along Borders with Neighbouring Countries;

- Economic and Infrastructure Backwardness; and

- Nonviable Nature of State finances.

SCS was granted based on an integrated consideration of these criteria.

In this report, we will delve into the historical background and criteria for SCS, benefits, contemporary issues and criticisms, and why states still demand SCS status, specifically focusing on Bihar’s demands.

Historical Background and Criteria:

Origins:

The Special Category Status (SCS) fundamentally relates to the determination of the allocation of Central Assistance for State Plans in India. The need for a rational and transparent allocation of Central Assistance to State Plans (CASP) became evident in the 1960s. The origins of SCS can be traced back to discussions related to the Gadgil formula during the Fourth Five-Year Plan in 1965, where several chief ministers emphasized the necessity for a structured approach to allocate central assistance to states with unique challenges. In December 1967, the National Development Council (NDC) convened to deliberate on the allocation criteria for central assistance. Although there was no unanimous agreement among the chief ministers on the specific criteria, yet there was a general feeling that States like Assam, Jammu & Kashmir and Nagaland would, in any way, have to receive special treatment.

In 1968, the Fifth Finance Commission was established to recommend the devolution of taxes and grants for 1969 -74. In its report submitted in 1969 highlighted significant disparities among states and emphasized the need for a redistributive policy beyond population-based grants. It considered Planning Commission transfers and recommended higher allocations for Assam, Jammu & Kashmir, and Nagaland to address these disparities.

Between 1969 and 1974, three states — Assam, Jammu & Kashmir, and Nagaland, received unusually high grants compared to others, marking them as “special” recipients of non-plan grants during that period.

Therefore, in the 26th meeting of the National Development Council held in April 1969, the needs of these three states were given priority over the other states by the Planning Commission as well. In terms of both plan and non-plan grants, they received much higher amounts compared to other Indian states, effectively treating these states as special. This decision marked these states as special cases and laid the foundation for the Gadgil formula and their Special Category Status conferred in 1969.

Note:

- The philosophy of SCS never emanated from any Finance Commission but from the resolution of erstwhile National Development Council.

- The decision to grant SCS lay with the National Development Council (NDC), which comprised the Prime Minister, Union Ministers, Chief Ministers, representatives of the UTs and members of the erstwhile Planning Commission. The NDC was the sole body competent to grant SCS, with no separate constitutional provisions, legislation, or executive orders governing this process. The NITI Aayog (National Institution for Transforming India), which replaced the Planning Commission, does not possess the authority to allocate funds.

Evolutions & Criteria:

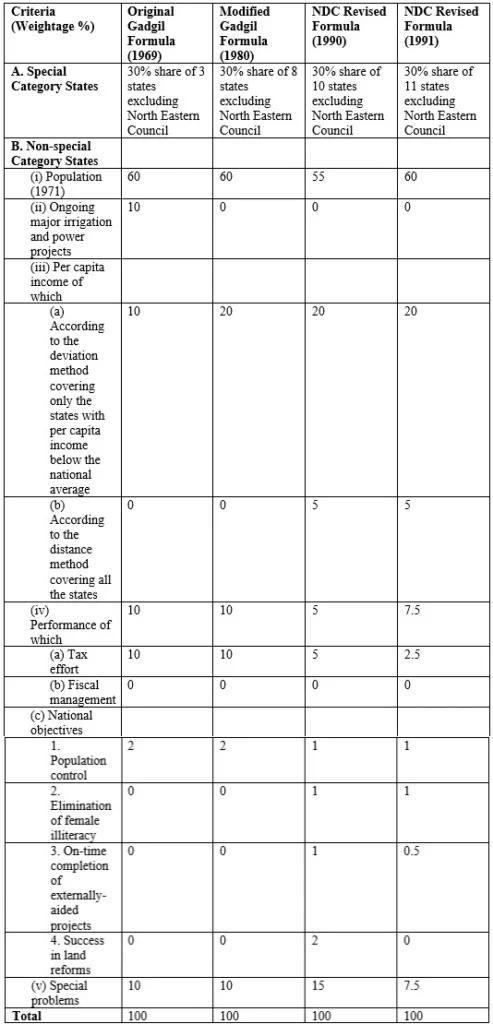

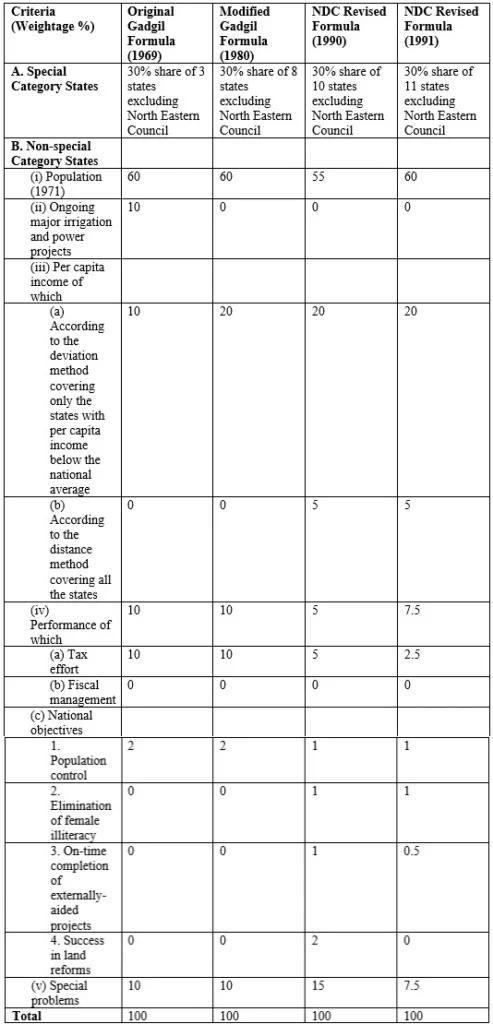

Before the Fourth Five-Year Plan (FYP), the allocation of CASP was determined by a schematic pattern lacking a definitive allocation formula. The states used to get more resources from the centre as loans and less as grants, plan and non-plan combined, leading to increasing indebtedness of the states. With the approval of Gadgil formula (named after Dhananjay Ramchandra Gadgil, the then deputy chairman of the Planning Commission) from the Fourth FYP, it led to the demand for a transparent and objective method for the horizontal distribution of resources among the States.

The Gadgil formula was applied for the first time in 1969. At that time there were altogether 17 states, among them, only three – Assam, Jammu & Kashmir, and Nagaland – were treated as special category states. By the Fifth FYP, the number of states had increased to 22, with all new states, except the original 14 (i.e. 17-3), given Special Category Status. Subsequently, various States were accorded SCS whenever they attained Statehood. These states were:

- Himachal Pradesh (1970-71)

- Manipur, Meghalaya, and Tripura (1971-72)

- Sikkim (1975-76)

- Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram (1986-87)

- Uttarakhand (2001-02)

Note:

- Telangana, which was bifurcated from Andhra Pradesh, was accorded SCS in 2014. However, the 14th Finance Commission, whose recommendations were implemented in the subsequent year, recommended phasing out this status except for the northeastern states and three hilly states: Jammu & Kashmir (now UT), Uttarakhand, and Himachal Pradesh.

The Gadgil Formula, initially employed during the 4th and 5th FYP (1969-78), allocated funds based on Population, Per Capita Income, Tax Effort, Ongoing Irrigation & Power Projects, and Special Problems. Due to biases favouring wealthier states, it was revised in 1980 and further refined to the Gadgil-Mukherjee Formula in 1991 and was approved by NDC, guiding allocations from the 8th FYP onward.

Later in 2013, Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS) underwent restructuring into six “core of the core” schemes and 22 “core” schemes, leading to subsequent proliferation. The 2015-16 budget saw the elimination of the Normal Central Assistance (NCA), and from 2017-18 onwards, the distinction between plan and non-plan expenditures was dissolved, effectively rendering the Gadgil formula obsolete in the evolving fiscal framework.

Benefits:

The Planning Commission allocated funds to states through three main components:

- Normal Central Assistance (NCA),

- Additional Central Assistance (ACA), and

- Special Central Assistance (SCA).

• The classification of a state as either Special Category or non-special category (General Category) determines the grant-loan ratio applicable for Normal Central Assistance (NCA). Special Category States received 30% of NCA, with 90% of this as grants and 10% as loans, while non-special category states shared the remaining 70% with a 30:70 grant-loan ratio.

• Allocation among Special Category States was based on plan size and previous expenditures, while the Gadgil-Mukherjee formula guided distribution among non-special category states.

• Special Category States also receive specific assistance addressing features like hill areas, tribal sub-plans and border areas.

• Special Category States can benefit from government-determined concessions on excise and customs duties, income tax rates, and corporate tax rates.

• Special Category States are provided Special Plan Assistance for projects of special importance to the State.

• Special Category States are provided with Special Central Assistance (SCA) untied to specific projects due to their challenging financial circumstances.

Issues & Criticism in granting Special Category Status:

Changing Dynamics:

- The 14th Finance Commission (FC-XIV 2015-20) recommended increasing the States’ share of the divisible pool of central taxes from 32% to 42%. The 15th Finance Commission (FC-XV 2021-26) has maintained the tax devolution at nearly the same level (i.e. at 41% with 1% adjustment for J&K and Ladakh). The Central Government asserts that higher tax devolution grants states more resources. From the 14th Finance Commission onwards, States got much more fiscal space to spend on their own priorities, instead of depending on the Centre.

- The report submitted by the FC-XIV in December 2014 did not make any specific recommendations for the Special Category Status. This omission gives the impression that the SCS has, in practice, been abolished.

- Normal Central Assistance (NCA) was allocated based on the Gadgil-Mukherjee Formula and distributed in 12 monthly instalments by the Ministry of Finance. From April 1, 2015, NCA allocations ceased due to the 14th Finance Commission’s recommendation, which increased the States’ share in the divisible tax revenues of the Centre by 10 percentage points. This significant increase in untied tax devolution accounts for both plan and non-plan revenue expenditures, effectively replaced the need for NCA.

- The introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017 also eliminated many of the tax benefits associated with the Special Category Status.

Perpetual Assistance with No Accountability:

- Once awarded, the special category status ensures a perpetual assistance pattern without specifying goals or timelines. It carries rewards for the state without obligations and is based solely on funding patterns, disregarding the state’s ability to utilize these funds effectively. This mechanism focuses on fund transfers without ensuring accountability, making it suboptimal for upliftment and empowerment. While some states have developed the capacity to leverage these resources, others have struggled due to factors like insurgency, political instability, and misgovernance.

Worsening resource position:

- The number of special category states increased from 3 during the formation to 11 in the end, but their share of total plan assistance remained at 30%, worsening their resource position.

- Finance commission grants had little impact on the resources of special category states, as the devolution of taxes from the divisible pool was formula-based, in which factors like population, area, fiscal discipline or tax effort mostly went against them. Their primary advantage came from plan grants, with non-plan grants being relatively insignificant despite continuing to help bridge revenue deficits.

Political considerations:

- The demand for SCS often becomes a political tool, with states lobbying for the status to gain additional funds. However, rather than being used for political mileage, this issue must be considered by a constitutional body to ensure impartiality and fairness. Such a body would be better equipped to evaluate the genuine needs and criteria for SCS designation, free from political pressures and influences.

Creates inequity among States:

- Critics argue that SCS creates inequity among states, with some benefiting disproportionately due to historical classifications.

Dependency Culture:

- There is a concern that SCS might foster a dependency culture, with states relying excessively on central assistance rather than developing their revenue-generating capacities.

Why do states still demand Special Category Status?

-__-

The core objective of the Finance Commission is to rectify vertical and horizontal fiscal imbalances within the country. The Finance Commission is required to recommend the distribution of the net proceeds of taxes of the Union between the Union and the States (commonly known as vertical devolution); and the allocation between the States of the respective shares of such proceeds (commonly known as horizontal devolution). Article 280(3)(a) of the Indian Constitution mandates the Finance Commission to recommend the distribution of the net proceeds of taxes from the divisible pool between the Union and the States.

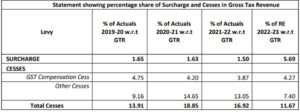

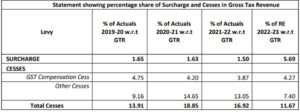

The divisible pool is that portion of Gross Tax Revenue (GTR) which is distributed between the Union and the States. Article 270 of the Constitution specifies the taxes which form the divisible pool. This consists of all taxes, except surcharges and cess levied for specific purpose (excluding the GST compensation cess) and tax revenue from the Union Territories, net of collection charges.

Now, it is important to note that the cess and surcharges revenue directly goes to the Centre and is not shared with States as devolution. Therefore, the more the cess and surcharges imposed and collected as proportion of the GTR, the less is the amount available for the States in the divisible pool.

For FY 2024-25, the GTR is projected to be ₹38.3 lakh crore with the states’ share being ₹12.2 lakh crore, constituting around 32% of the GTR as per the budget estimates. Thus, the finance commission formula for devolving 41% of the divisible pool appears far-fetched in practice.

This issue was also highlighted by the RBI in 2019, which observed that the share of revenue from cess and surcharge in the central government’s GTR has increased from 2.3% in 1980-81 to 15% in 2019-20. Moreover, in response to a question in the Lok Sabha in July 2023, the Centre released data indicating that from 2019-20 to 2022-23, cesses and surcharges (excluding GST Compensation Cess) comprised around 11-16% of the GTR collected.

Another reason why Special Category Status (SCS) remains a major demand among poorer states is because of higher taxes devolved to SCS states. As seen earlier, though the 14th Finance Commission did not explicitly address SCS, estimates indicate that the share of taxes devolved to SCS states was significantly higher. Data for 2022-23 reveal that gross transfers from the union government account for 67% of the overall budget disbursements in SCS states, compared to a much lower 34% in General Category States. This clearly demonstrates that, despite the official discontinuation of the SCS designation, the eight north-eastern and three Himalayan states still benefit from a disproportionately larger allocation of funds.

The shrinking fiscal space of states, despite their higher expenditure burden, coupled with the perpetual higher tax devolution to SCS states, are the primary reasons for demanding Special Category Status.

Bihar’s Demand for Special Category Status:

Bihar has long sought Special Category Status, primarily due to its economic backwardness, historical disadvantages and developmental challenges. Chief Minister Nitish Kumar has been a vocal advocate for this status since 2006, highlighting the state’s persistent poverty and lack of development.

To overcome its developmental challenges, here are a few reasons for demanding SCS and the present stance of Bihar’s case:

Economic backwardness:

- Bihar is identified as the poorest state in India according to the Centre’s Multi-dimensional Poverty Index (MPI), with 52% of its population lacking adequate health, education, and living standards. The state’s per capita income stands at around ₹54,000, which is among the lowest in the country. Additionally, a recent caste-based survey conducted in 2023 revealed that 34.13 per cent of the state’s population have a monthly income of ₹6,000 or less. This data underscores the acute economic distress faced by Bihar, making a compelling case for additional financial support through SCS.

Lacks Natural resources:

- The bifurcation of Bihar in November 2000 substantially impacted the state’s resource base. Most mineral wealth and revenue-generating assets were transferred to Jharkhand. Consequently, major industries and mining belts remained with Jharkhand, resulting in a significant reduction in employment and investment opportunities in Bihar. The lack of natural resources and coastline connectivity further hinders the state’s ability to attract private investment, necessitating special assistance or packages from the central government.

Natural Calamities:

- Bihar is highly susceptible to natural calamities, which severely impact its economic stability and development. The northern region of the state frequently suffers from devastating floods, while the southern part grapples with severe droughts. These recurring disasters disrupt agricultural activities, hinder irrigation facilities, and lead to inadequate water supply, affecting livelihoods and economic stability. The state’s vulnerability to natural calamities necessitates additional financial resources and special considerations to mitigate their impact.

Inadequate Infrastructure:

- Bihar’s inadequate infrastructure is a major impediment to its overall development. The state suffers from poor road and bridges networks, limited healthcare access, and challenges in educational facilities. These infrastructural deficiencies hamper economic activities and restrict social development. The Raghuram Rajan Committee, set up by the Centre in 2013, classified Bihar as one of the “least developed” states, highlighting the urgent need for targeted financial assistance.

NITI Aayog’s Reports Stance:

The latest report of NITI Aayog’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) India Index 2023-24 vindicated Bihar’s long-standing demand for greater central financial assistance. Despite some improvements, Bihar ranked at the bottom of the SDG India Index, highlighting the state’s persistent developmental challenges. The report underscores the necessity for special financial assistance, either through SCS or a special package, to enable Bihar to manage its finances effectively.

Central Government’s Stance:

The Centre has stated that Special Category Status to any state is granted based on specific criteria, and Bihar’s request for SCS was denied in 2012. In a written reply to the Lok Sabha on 22 July 2024, the government cited an Inter-Ministerial Group (IMG) report prepared in March 2012 to assert that a case for granting special category status to Bihar is not made out. The IMG, which reviewed Bihar’s request, concluded in its report that Bihar’s case for SCS does not fulfil the NDC criteria.

©bpscexamprep.com

Way forward:

The Special Category Status has played a crucial role in the equitable distribution of central assistance, particularly for states facing significant geographical and socio-economic challenges. While it has helped bridge regional disparities, the evolving criteria and the inclusion of new states continue to be subjects of debate. Bihar’s persistent demand for SCS highlights the need for a nuanced approach to addressing the developmental needs of backward states. The focus remains on ensuring that states with genuine needs receive the necessary support either in form of special category status or special package to overcome their developmental hurdles, fostering balanced and inclusive growth across India.

***